Oct 20, 2015

Asian Art Museum presents European, American, and Japanese masterpieces in exhibition exploring the impact of Japan on Western artists.

Download a PDF copy of this Press Release | Public Programs

SAN FRANCISCO, Oct. 20, 2015—Japan’s opening to international trade in the 1850s after two centuries of self-imposed isolation set off a craze for all things Japanese among European and North American collectors, artists and designers. The phenomenon, dubbed japonisme by French writers, radically altered the course of Western art in the modern era. San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum surveys this sweeping development in the traveling exhibition Looking East: How Japan Inspired Monet, Van Gogh, and Other Western Artists. The exhibition traces the West’s growing fascination with Japan, the collecting of Japanese objects, and the exploration of Japanese subject matter and styles. Looking East will be on view from Oct. 30, 2015–Feb. 7, 2016 with the exhibition’s final weeks marking the start of the museum’s 50th anniversary year in 2016.

Looking East features more than 170 artworks drawn from the acclaimed collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, with masterpieces by the great Impressionist and post-Impressionist painters Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas and Paul Gauguin, among others. The art and culture of Japan inspired leading artists throughout Europe and the United States to create works of renewed vision and singular beauty.

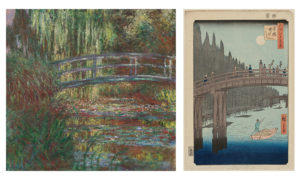

The exhibition is organized into four thematic areas, tracing the impact of Japanese approaches to women, city life, nature and landscape. Within each theme, artworks from Japan are paired with American or European works to represent the West’s assimilation of new thematic and formal approaches. Japanese woodblock prints by such celebrated masters as Kitagawa Utamaro, Utagawa Hiroshige and Katsushika Hokusai are shown in dialogue with oil paintings, prints and photographs by a diverse mix of Western artists, demonstrating regional variations on japonisme. Bronze sword guards and paper stencils from Japan are juxtaposed with metalwork by Western manufacturers Boucheron, Gorham and Tiffany. Other objects used in daily life, like a chair designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, also show the wide-ranging impact of Japanese design in the West.

Additional highlights in the exhibition include Vincent van Gogh’s painting Postman Joseph Roulin; Claude Monet’s The water lily pond; Five Swans, an elegant wool tapestry designed by Otto Eckmann; Paul Gauguin’s canvas Landscape with two Breton women; and Otome, a print by Kikukawa Eizan.

“Everything the Asian Art Museum does—exhibitions, programs, events, outreach— directly links back to our vision: With Asia as our lens and art as our cornerstone, we spark connections across cultures and through time, igniting curiosity, conversation and creativity,” said Asian Art Museum director and CEO Dr. Jay Xu. “One way we spark these connections is by exploring Asia’s global relevance. Looking East is a perfect example of this. For the first time, the museum will present great Western artists, like Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh and Mary Cassatt, who were moved by Japanese art and culture.”

Organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the exhibition was curated by Dr. Helen Burnham, the Pamela and Peter Voss Curator of Prints and Drawings from MFA, Boston. The exhibition premiered at Nashville’s Frist Center for the Visual Arts, followed by a tour in Japan and then a stop at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec. The Asian Art Museum’s presentation, curated by Dr. Laura Allen, curator of Japanese art, and Dr. Yuki Morishima, assistant curator of Japanese art, is the final stop on the exhibition’s international tour.

Visitors are encouraged to begin their journey in the museum’s Osher Gallery, followed by Hambrecht Gallery and then Lee Gallery.

By the late 1870s, Westerners curious about Japan could encounter its art and artifacts in many places, including specialty shops, World’s Fairs and exhibitions. Osher Gallery introduces visitors to the many ways Western artists engaged with Japanese art, with a focus on depictions of women and city life.

Western women played a role in japonisme as enthusiastic collectors, as models costumed in Japanese robes or posed in proximity to imported screens and vases, and as artists. Paintings of European beauties in imported kimonos signaled to viewers that the women were fashionable, yet also sensual beings. Many Westerners of the time associated kimonos with the courtesans and geisha familiar from Japanese “floating world” prints (ukiyo-e). Japanese artists’ frank portrayal of the most intimate or everyday activities of their female subjects also inspired similar experiments in the work of Western artists. Kikukawa Eizan’s Otome is an example of the type of prints Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844–1926) drew upon in works such as Maternal Caress (Caresse maternelle) and Under the Horse Chestnut Tree.

The bustling city views featured in many Japanese prints encouraged Western artists to pursue new ways of presenting modern urban life. Of particular note was a series of 119 prints depicting places in Edo (modern Tokyo), One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, created by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858). In Kinryuzan Temple, Asakusa Hiroshige radically enlarged a large red lantern and gatepost, pushing them flat against the picture plane where they frame a view into space. Poster designers in France and America borrowed similar techniques to create bold, graphic emblems of modern urban life, such as The Century, July 1895, a poster by American artist Charles Herbert Woodbury (1864–1940).

Japanese prints depicting urban stars of the Kabuki theater encouraged novel approaches to the art of portraiture. The striking, angular pose and intense gaze of actor portraits like Onoe Matsusuke II by Utagawa Kunisada I (1786–1864) may have inspired similar features in the work of Vincent van Gogh. In Van Gogh’s Postman Joseph Roulin, the artist employed bright colors and stylized forms like those he found in the Japanese prints he admired and collected.

Nature-based motifs in prints, lacquerware and metal objects from Japan initiated creative new pathways in the Western decorative arts and new subjects for a growing cadre of Western printmakers and photographers. Artists and collectors welcomed these references to nature, using them to revitalize domestic interiors and incorporating them into skillfully designed rooms. In the United States, Tiffany Studios spread Japanese-style designs through lamps, stained-glass windows and a line of affordable household objects. The letter rack shown in this gallery, made of metal and iridescent glass, is decorated with a stencil-like grapevine design likely derived from Japanese textile patterns, or katagami.

Among the many movements featuring Japanese-inspired modes of representing the earth and its creatures, Art Nouveau stands out for its abstract treatment of natural forms. Five Swans, an elegant wool tapestry designed by Otto Eckmann, is an icon of German Art Nouveau, or Jugendstil. Its bold, winding outlines, long vertical format, abstraction, and geometric patterning borrow from Japanese woodblock prints and hanging-scroll paintings, as well as from the decorative lines and patterns of medieval German tapestries and prints.

For landscape painters seeking alternatives to the academic orthodoxies of the West, the novel perspectives, bold colors and rhythmic two-dimensional patterns of Japanese prints provided powerful stimuli. Instead of using shadows to create convincing three-dimensional forms, the Japanese employed contrasts in color, repeated shapes and a focus on essential features to animate views of such iconic sites as Mount Fuji. These pictorial devices soon became part of the Western artist’s toolbox.

Claude Monet’s (1840–1926) work is a highlight of the Landscape section. Monet absorbed not only pictorial lessons but also a distinct sensibility from his study of Japanese masters, the only artists with whom he wished to be compared. In conversation with a critic in 1909, Monet stated: “If you insist on forcing me into an affiliation with anyone else . . . then compare me with the old Japanese masters; their exquisite taste has always delighted me, and I like the suggestive quality of their aesthetic, which evokes presence by a shadow and the whole by the part.”

Monet was one of several artists of the time to explore close-up views of water juxtaposed with a building, bridge or vegetation. This is a subject familiar from Japanese art, as can be seen in Utagawa Hiroshige’s print Bamboo Yards, Kyobashi Bridge. A similar theme is reprised in The water lily pond, one of a number of paintings by Monet to feature his garden and its water lily pond with a Japanese-style curved footbridge.

In Monet’s paintings Seacoast at Trouville and Haystack (sunset), the landscapes’ carefully balanced compositions and vivid colors, their striking, silhouetted motifs and flattened space, incorporate lessons from Japanese prints, filtered through Monet’s unique vision of the natural world. A comparison of the composition of Seacoast at Trouville to Utagawa Hiroshige’s well-known Yokkaichi: Mie River suggests how Monet adapted elements from Japanese art to his own creative ends.

In addition to Monet, Paul Gauguin held an interest in Japanese prints and was an enthusiastic collector. In Gauguin’s painting Landscape with two Breton women, the extremely flattened space, the asymmetry of the composition, and its interlocking areas of flat color echo effects seen in Japanese prints.

Other Japanese elements incorporated into the new Western styles were the repeated trees, trellises and grid-like structures that offered a new way of organizing landscape that was legible while also being decorative or symbolic. In the print Hodogaya on the Tokaido, Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) uses rows of trees both as background for the drawings of various kinds of travelers that populate the foreground, and as a framing device for the view of Mount Fuji in the far distance. These ingenious techniques for creating pictorial space inspired similar experimentation in the work of Western artists. For example, Edvard Munch’s (1863–1944) mesmerizing painting Summer Night’s Dream portrays vertically aligned trees likely derived from Japanese art, either as he directly encountered it in Paris or as transmitted by earlier European painters who had incorporated such lessons into their work. In Munch’s painting, the trees demarcate an alternative realm, the emotional sphere of sexual awakening, embodied by a young, ghostly woman in a moonlit park.

Looking East: How Japan Inspired Monet, Van Gogh, and Other Western Artists was organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Presentation is made possible with the generous support of Mr. and Mrs. William K. Bowes Jr., The Bernard Osher Foundation, Diane B. Wilsey, The Henri and Tomoye Takahashi Charitable Foundation, United Airlines, Estate of Kazuko Imagawa Zolinsky, The Akiko Yamazaki and Jerry Yang Fund for Excellence in Exhibitions and Presentations, Robert Lehman Foundation, Union Bank, and Toshiba International Foundation. This exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Art and the Humanities.

A catalogue accompanies the Looking East exhibition, published by MFA Publications (available in hardcover, $29.95; 128 pages). Available at the Asian Art Museum store: 415.591.3600, [email protected] or http://store.asianart.org.

The Asian Art Museum—Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture is one of San Francisco’s premier arts institutions and home to a world-renowned collection of more than 18,000 Asian art treasures spanning 6,000 years of history. Through rich art experiences, centered on historic and contemporary artworks, the Asian Art Museum unlocks the past for visitors, bringing it to life while serving as a catalyst for new art, new creativity and new thinking.

Information: 415.581.3500 or www.asianart.org

Location: 200 Larkin Street, San Francisco, CA 94102

Hours: The museum is open Tuesdays through Sundays from 10 AM to 5 PM. During spring and summer, hours are extended on Thursdays until 9 PM. Closed Mondays, as well as New Year’s Day, Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day.

Looking East Admission: FREE for museum members and children (12 & under). On weekdays, $20 for adults and $15 for seniors (65 & over), youth (13–17) and college students (with ID). On weekends, $25 for adults and $20 for seniors (65 & over), youth (13–17) and college students (with ID). On Target First Free Sundays, admission is $10.

General Admission: FREE for museum members, $15 for adults, $10 for seniors (65+), college students with ID, and youths (13–17). FREE for children under 12 and SFUSD students with ID. General admission on Thursdays after 5 PM is $5 for all visitors (except those under 12, SFUSD students and museum members, who are always admitted FREE). General admission is FREE to all on Target First Free Sundays (the first Sunday of every month).

Access: The Asian Art Museum is wheelchair accessible. For more information regarding access: 415.581.3598; TDD: 415.861.2035.

###