Feb 13, 2015

Escape to Japan’s floating world through a selection of rare paintings, woodblock prints and kimonos at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum.

Download a PDF copy of this Press Release | Public Programs

SAN FRANCISCO, Feb. 13, 2015—Seduction: Japan’s Floating World transports viewers to the popular and enticing entertainment districts established in Edo (present-day Tokyo) in the mid-1600s. Through more than 50 artworks from the acclaimed John C. Weber Collection, visitors can encounter the alluring realm known as the “floating world,” notably its famed pleasure quarter, the Yoshiwara. Masterpieces of painting, luxurious Japanese robes, woodblock-printed guides and decorative arts tell the story of how the art made to represent Edo’s seductive courtesans, flashy Kabuki actors and extravagant customs gratified fantasies and fueled desires.

At a time when a strict social hierarchy regulated most aspects of the samurai and townsmen’s lives, the floating world provided a temporary escape. The term “floating world,” or ukiyo, originated from a common Buddhist phrase referring to the suffering of the physical world, which was inverted to signify a realm of boundless indulgence. Both a state of mind and a set of locales, the floating world refers to the diversions available in the brothel districts and Kabuki theaters of Edo, a city whose population had reached a million by the beginning of the 18th century. The floating world’s rise to prominence gave birth to an outpouring of new artistic production, in the form of paintings and woodblock prints that advertised celebrities and spread knowledge of the city’s famous theaters and brothels. One spectacular example is the exhibition’s centerpiece, an almost-58-foot long, richly detailed handscroll painting of life in the Yoshiwara.

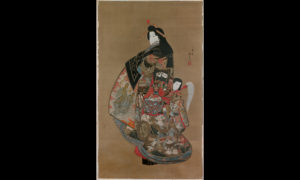

Other exhibition highlights include 18th-and 19th-century paintings and prints by some of the most talented artists of the time: Katsukawa Shunsho (d. 1792), Kitagawa Utamaro (1754–1806), Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) and Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797–1861). Their subjects are the courtesans and actors celebrated as stars of the floating world. Sensual poses, extravagant fashions and clever disguises are some of the techniques artists used to amplify the seductive power of their paintings, luring potential patrons to the city’s theaters or providing consoling substitutes for absent objects of desire.

“Seduction introduces visitors to the exquisite style of Japan’s Edo period,” said Jay Xu, director of the Asian Art Museum. “The floating world led to incredible innovation in the arts of unparalleled beauty and poignancy, and the artworks themselves continue to intrigue and seduce.”

The exhibition begins in the museum’s Hambrecht Gallery and continues in Osher Gallery. It will be shown alongside a complementary exhibition in the museum’s Lee Gallery titled The Printer’s Eye: Ukiyo-e from the Grabhorn Collection, which focuses on the artistic achievements of Edo-period (1615–1868) printmakers. Both exhibitions are on view Feb. 20–May 10, 2015.

Organized by the Asian Art Museum, Seduction is curated by Dr. Laura Allen, curator of Japanese art.

Hambrecht Gallery: Introduction to the Yoshiwara

The Yoshiwara was the sole licensed red-light district of Edo, teeming with teahouses, shops and more than a hundred brothels. Museum visitors can go on an imaginative virtual tour of the Yoshiwara by viewing “A visit to the Yoshiwara” (cat. no. 1), a grand, nearly-58-foot-long handscroll painting by the foremost 17th-century artist of floating-world pictures, Hishikawa Moronobu. Viewers can use an interactive iPad app to magnify the scroll’s details and its almost 400 figures, including showy courtesans, musicians, maids, chefs preparing a banquet, and sword-carrying samurai disguised with straw hats to evade the restrictions on warriors entering the pleasure quarter.

The scroll consists of a sequence of 15 scenes in which viewers approach the Yoshiwara’s main gate, view the street life of the quarter, and visit various brothels. The culminating episode takes place at a lavishly decorated house of assignation (ageya) where wealthy samurai are entertained by highly skilled courtesans.

In one scene, a couple is shown snuggling under a bed cover in a Yoshiwara teahouse. A client’s gift of bed covers to a courtesan was a means of claiming a special relationship with her, and the bedding was for their exclusive use. A kimono-shaped bed cover (cat. no. 30) with an elegant phoenix design can be viewed in this gallery.

Other objects in this gallery, including a woman’s luxurious red silk outer robe (cat. no. 31), an elegant pear-form bottle (cat. no. 54) and a lavishly decorated lacquer mirror stand (cat. no. 48), represent the types of sophisticated furnishings and textiles used to create an ambience of luxury in the Yoshiwara’s most expensive establishments.

Osher Gallery: Intimacy, Fashion and Disguise

By the end of the 18th century, more than 4,000 prostitutes worked in the Yoshiwara. Many prostitutes started life as girls from impoverished homes in the countryside, bought from their families, taken to the quarter at age 7 or 8, trained, and bound to the brothel owners during the term of contracts lasting roughly ten years. While the tiny minority of elite courtesans may have led relatively comfortable lives, with fancy clothes and access to teachers, most Yoshiwara women were not so fortunate. Edo sex workers were subject to daily quotas; unwanted pregnancies and venereal disease were endemic. From today’s perspective these women were sexually exploited in a system of forced and strictly controlled prostitution.

Yoshiwara women were ranked by brothel owners in a hierarchy ranging from the lowly moat-side prostitutes whose services were quick and inexpensive to the top-ranked courtesans, who were accessible only through a rigorous set of protocols, requiring huge payments and tips at three preliminary meetings. Highly trained in music, calligraphy, poetry and other refined arts, the top-ranked courtesans emerged as celebrities. Much admired throughout Edo for their beauty and style, they were the subjects of literature, paintings and countless woodblock prints. Not surprisingly, most artists at the time glossed over the more sordid and sad truths of Yoshiwara life in favor of artfully constructed fantasies.

Many pictures of courtesans convey a sense of promised intimacy or romance, to whet the appetites of male clients and remind clients of courtesans when they were apart. Osher Gallery features several paintings with these types of scenes: courtesans waiting for their next clients in the evening rain (cat. no. 20); a courtesan scantily dressed in her boudoir (cat. no. 18); a couple in a close embrace (cat. no. 7); and a woman reading a letter possibly from an admirer (cat. no. 8).

In addition to the paintings and prints focused on courtesans, books such as Mirror of the Yoshiwara (cat. no. 59) offered readers an intimate glimpse into the private lives of the period’s most renowned courtesans. This book in particular contains commentaries on the 28 top-ranked courtesans and details of the pleasure quarter.

In courtesan pictures, fashion is also closely allied with seduction. Artists used elaborate fabrics and up-to-date styles to symbolize a courtesan’s status in the pleasure quarter and her ability to command the attention of wealthy clients, as in the painting of a courtesan promenading under cherry blossoms (cat. no. 17) by artist Katsushika Hokuun (active approx. 1800–1844). While few courtesan costumes survive today, Osher Gallery includes several exquisite robes made for samurai-class women and wealthy merchant wives as vibrant evidence of the beauty, variety and technical grandeur of Edo-period styles.

Other works in the exhibition use cross-dressing, theatrical costumes and disguise as aspects of their seductive power. In Kabuki, the popular stage art of the time, women were prohibited by law from acting in plays. Women’s roles were therefore performed by male actors costumed in feminine attire. Included here are paintings of Kabuki actors costumed for the stage, as seen in a painting of a female impersonator (cat. no. 4).

The exhibition concludes with the imposing portrait of Hell Courtesan (cat. no. 21), by Utagawa Kuniyoshi. This legendary 15th-century prostitute, who was guided to enlightenment by a Zen monk, wears a dramatic costume depicting scenes of hell— bringing us full circle to the Buddhist sense of ukiyo as suffering prompted by desire.

The Asian Art Museum will serve as the only venue for the exhibition.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a substantive, richly illustrated catalogue, published by the Asian Art Museum; available in hardcover, $50; and softcover, $35, 259 pages. Available soon at the Asian Art Museum store: http://store.asianart.org or 415.581.3600 or [email protected].

Seduction: Japan’s Floating World | The John C. Weber Collection was organized by the Asian Art Museum. Presentation is made possible with the generous support of Hiro Ogawa, Atsuhiko and Ina Goodwin Tateuchi Foundation, The Henri and Tomoye Takahashi Charitable Foundation, The Akiko Yamazaki and Jerry Yang Fund for Excellence in Exhibitions and Presentations, Anne and Timothy Kahn, Rhoda and Richard Mesker, and Blakemore Foundation. Media sponsors: ABC7, SF Media Co., KQED, and San Francisco magazine.

The Asian Art Museum–Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture is one of San Francisco’s premier arts institutions and home to a world-renowned collection of more than 18,000 Asian art treasures spanning 6,000 years of history. Through rich art experiences, centered on historic and contemporary artworks, the Asian Art Museum unlocks the past for visitors, bringing it to life while serving as a catalyst for new art, new creativity and new thinking.

Information: 415.581.3500 or www.asianart.org

Location: 200 Larkin Street, San Francisco, CA 94102

Hours: The museum is open Tuesdays through Sundays from 10 AM to 5 PM. From Feb. 26 through Oct. 8, the museum is open on Thursdays until 9 PM. Closed Mondays, as well as New Year’s Day, Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day.

General Admission: FREE for museum members, $15 for adults, $10 for seniors (65+), college students with ID, and youths (13–17). FREE for children under 12 and SFUSD students with ID. General admission on Thursdays after 5 PM is $5 for all visitors (except those under 12, SFUSD students, and museum members, who are always admitted FREE). General admission is FREE to all on Target First Free Sundays (the first Sunday of every month). A surcharge may apply for admission to special exhibitions.

Access: The Asian Art Museum is wheelchair accessible. For more information regarding access: 415.581.3598; TDD: 415.861.2035.

###